“Throughout our Nation’s history, American women have led movements for social and economic justice, made groundbreaking scientific discoveries, enriched our culture with stunning works of art and literature, and charted bold directions in our foreign policy.”

In 2009, Martha Ulman, Clara Spence’s grand-daughter, wrote an article for the New York State Historical Association chronicling the history of her grandmother’s achievements as a pioneer in adoption in New York. We can think of no better way to acknowledge the women who shaped social justice than to honor our own founder and adoption advocate Clara Spence. This is an excerpt from Martha Ulman’s article: Clara Spence

Clara Spence achieved her work during the pivotal decades 1900-1920, when there were many people with socially progressive ideas. Some approached the problem of the discrepancy between the rich and the poor from the bottom up. They personally went into the slums and worked with the problem firsthand. Clara Spence chose to approach the problem from the top by preaching to the children of the richest New Yorkers the moral and ethical virtue of service so that they, in their adult life, would make a difference in improving the conditions of those less fortunate. Although many of her students went own to serve in their communities, the area for which they are best known is that of adoption and the creation of their nursery, which merged with that of Henry and Alice Chapin in 1943. Known today as Spence-Chapin Services to Families and Children, the organization continues to serve the needs of children of all creeds, colors, and nationalities.

Born in Albany, New York, in 1859, Clara Spence was a member of the middle class. She graduated from Boston University’s School of Oratory in 1879, after which she attended London University where she honed her acting skills. She came to New York City originally aspiring to be an actress but, upon the death of her mother in 1883, she shifted her talents to teaching at private schools for girls. In 1892, she founded her own school in a brownstone at 6 West Forty-Eighth Street. It was in this school that Clara Spence began a nursery for abandoned babies.

The treatment of orphans before the 1890’s followed a dreary route from institutional care to indentured service or, in the case of thousands of children in Charles Loring Brace’s orphan trains, relocation to families hundreds of miles from their homes. There, as Marilyn Holt notes in her book, “The Orphan Trains: Placing Out in America”, they were often valued for their labor potential rather than accepted as members of the family. Clara Spence offered adoption as an alternative to institutionalization or relocation. Adoption, which we now take for granted, was an anomaly at a time when to adopt a non-relative was consider a brave and bizarre act, because of genetic uncertainty and social stigma. Clara Spence dedicated herself to the cause of abandoned infants and introduced her students to adoption as a new and fulfilling form of social work.

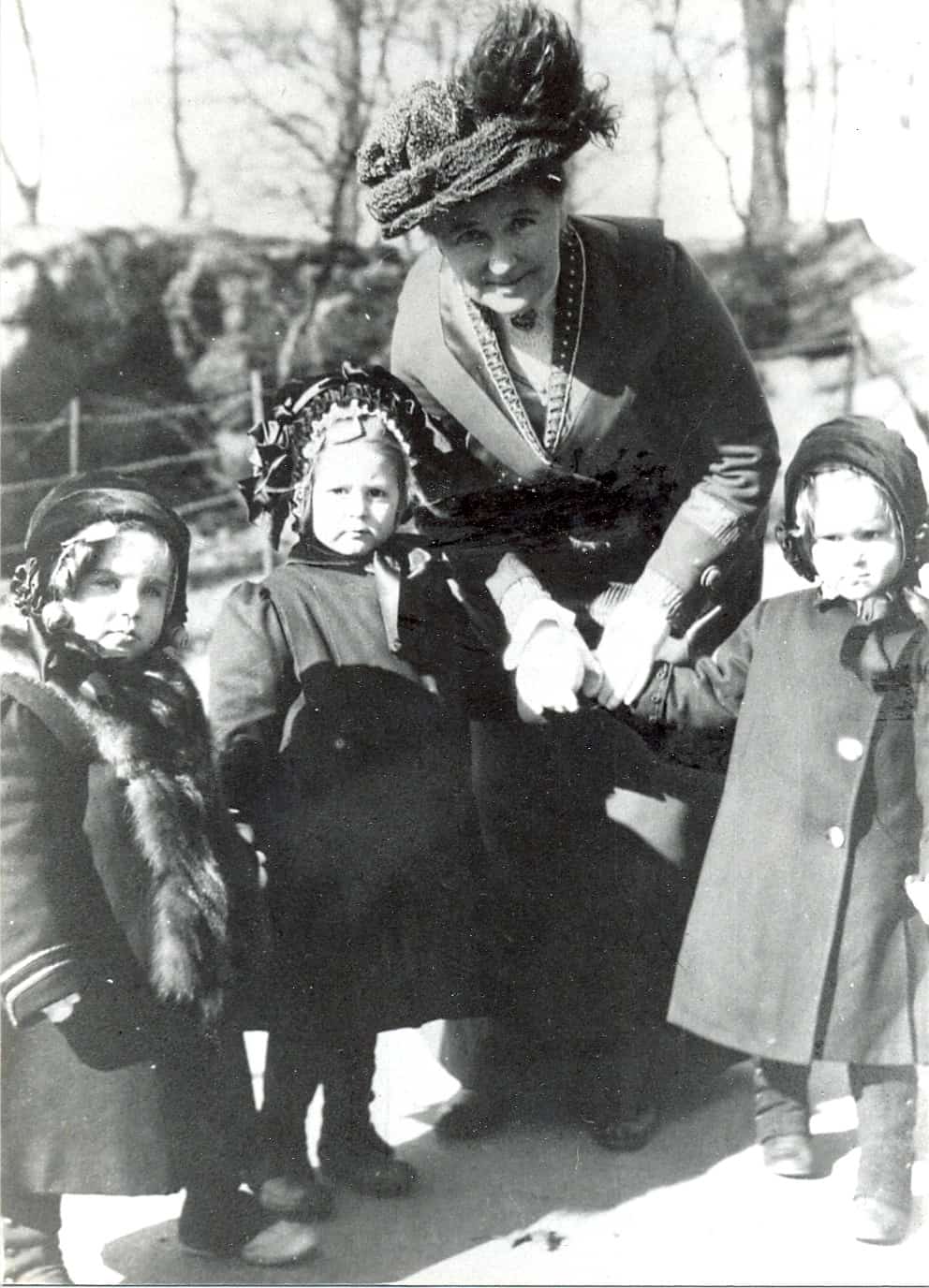

Clara Spence – Central Park, February 1911

In January 1909, the White House Conference on Dependent Children adopted fourteen resolutions all aimed at replacing the institutional method of child care with home care. The next month Clara Spence personally adopted a one-year-old girl from the Children’s Aid Society. The judge had no objection to her application even though she was a single parent nearing the age of fifty. Six years later in 1915, Clara Spence adopted a little boy. Her partner, Charlotte Baker, adopted a girl in 1911 and a boy in 1914, completing what was one of the first single-sex adoption families.

It was Ms. Spence’s personal involvement that inspired her students, who witnessed the transformation of babies who came from institutions and were “built up” for adoption on the top floor of her school. As a result, in 1915, the alumnae of the school opened the Spence Alumnae Society nursery through which several hundred babies were placed in adoptive homes. In 1921, Clara Spence brought thirteen children from Great Britain to the United States to be adopted into American families, anticipating what has today become a vast network of international adoption. By her willingness to defy public opinion and risk social ostracism, Clara Spence not only managed to make adoption an accepted practice, but one that became the method of choice for hundreds of families. It was largely because of her work and influence that New York became recognized as a leader in child welfare and adoption in particular.

Spence-Chapin has spent over 100 years finding innovative ways to fulfill Clara Spence’s legacy. Our expertise has consistently expanded the benefits of adoption to more children and the prospective parents who want to love them.

Just as Clara Spence responded to the need in her time, our work is focused on serving women and families who need help planning and building strong, loving families. We are driven by the simple and fundamental belief: every child deserves a family. Through our Modern Family Center, we provide counseling and community services that help these new families succeed. We can create more permanent, loving families just as we’ve always done.